A Riot in the Forest

In 1831 serious disturbances occurred in the Forest of Dean, and a great deal of damage to public and private property was done by the rioters, of which a detailed account may be seen in a pamphlet published by Heath, the Monmouth Antiquary. The agitation was led by one, Warren James, known as the Champion of the Forest, and arose from a mistaken idea about the Act of 1808, by which authority the Forest was enclosed. The provisions were the same as those of an Act of Charles II, by which eleven thousand acres should be always set apart for the preservation of timber for the Navy, and fenced in to protect the young trees from cattle, until old enough to take care of themselves. The enclosures were then to be thrown open, that the Foresters might resume those grazing rights of which they were exceedingly jealous. An idea got abroad that they were being improperly deprived of these rights by the fences being kept up too long, and the agitation being actively fanned by James, great numbers of Foresters assembled on the 8th of June and proceeded to destroy the boundary walls and the gardens and crops growing round the woodmen's cottages, on the ground they considered should be common land. It was deemed necessary to call in military aid and Captain Kane, and Captain Mitohel of the Royal Marines who was on recruiting duty at Monmouth, were ordered to march to Coleford with what force they could muster. It is a tradition that the Royal Monmouth Militia were employed, and that the expedition was a ludicrous failure, and it is only fair to the Regiment to state what the facts really were. Captain Kane at once sent a sergeant by post to Hereford to borrow ammunition. The messenger returned with nothing but 100 flints. Captain Kane then sat up all night, with Sergeant Major Jones, casting bullets, and next morning they marched out with a force they had rapidly organised of about 50 pensioners and recruits. They had no uniforms but had belts on over their plain clothes. Captain Kane was afterwards commended for his energy and tact, and was by no means responsible for the inadequacy of the force at his disposal.

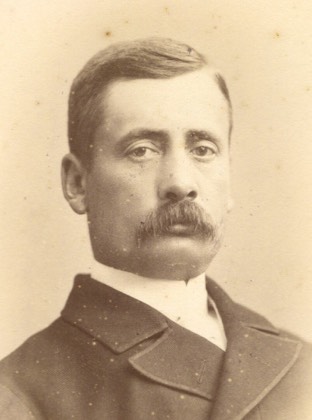

Capt W F N Noel

Arrived at Coleford he perceived affairs to be too serious, and the crowds of Foresters too large and threatening to be dispersed by the mere show of a body so little imposing, and therefore marched the men into the Town Hall, and posted a guard on the door. Next day there was a good deal of shouting and rough chaff, and Captain Kane and his party returned to Monmouth. The 3rd Dragoons marched into Coleford the same day, and the Duke of Beaufort, Lord Worcester and a body of the county magistrates having assembled, Warren James, who was only a vapouring agitator, hid on the show of force, but was at once betrayed and caught.

The following letter was forwarded to Captain Kane :- "The Magistrates assembled at Coleford cannot allow Captain Kane and Captain Mitchell, with the men under their command, to return home without begging these officers to accept of their best thanks for the ready manner in which they complied with the wishes of the Magistrates to attend at Coleford in aid of the Civil Power, and for the active and attentive manner in which they have performed the duty imposed upon them, and they request the officers will be so good as to explain to the non-commissioned officers and men under their command how highly the Magistrates approve of their conduct.”

Warren James was tried and sentenced to death, though this was commuted to transportation for life. Local petitioning then led to a pardon, but without a free passage, and he died in Tasmania in 1841. Nine of his comrades went to prison. But within a decade some rights for the Free Miners were enshrined in law.